Symbols

The symbols used in the mandala shown are all standard Christian symbols for God, the Trinity, and the three persons of the Trinity.

Circle – God

Triangle – The Trinity, one God in three persons

Hand – God the Father, the small circle indicates divinity

Dove – God the Holy Spirit, the small circle indicates divinity

Risen Christ – God the Son, the small circle indicates divinity

Part 2

We have three very consistent verses from different books of the New Testament:

Hebrews 1:2 – but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son, whom he appointed the heir of all things, through whom also he created the world.

John 1:3 – All things were made through him [the Son], and without him was not any thing made that was made.

Colossians 1:15-16 – 15 He [the Son] is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation. 16 For by means of him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or authorities—all things were created through him and for him.

All three persons of the Trinity acted in the creation. The Father is the creator, the Son is the agent of creation, and the Holy Spirit hovered over the waters. In other words, the Son is the active cause that brought into being the universe according to the plan conceived in the Father’s mind. The Son acts as the Father’s agent or instrument.

According to the New Testament writers, creation was made through the Son. Why was this truth taught, and how was it arrived at?

Understanding the Son’s role in creation isn’t mission critical to your salvation, but the topic is fascinating. The following is a very short answer to the question above, providing an introduction to this subject area. I hope you come away with a broader appreciation of the New Testament authors.

Greek thought, philosophy, and language flourished during the Roman empire in the Mediterranean world. From Earle Cairns’ book, Christianity Through the Centuries, “The Romans may have been the political conquerors of the Greeks, but as Horace indicated in his poetry, the Greeks conquered the Romans culturally. The practical Roman may have built good roads, mighty bridges and fine public buildings, but the Greek reared lofty edifices of the mind.”

Recall, the New Testament was originally written in Greek, rather than Hebrew, making the text accessible to Hellenistic or Greek-speaking Jews and the large numbers of Greek-speaking Gentiles coming into the Christian church. The Greek language was necessary so that the Gospel could expand outside of Palestine, first to Hellenistic Jews and then to Greek-speaking Gentiles. Hellenists are first mentioned in Acts 6:1. In the New Testament, Hellenists refer to Greek-speaking Jews.

The Gospel of John, chapter 1. The subject of the Logos had a long prior history in Greek Philosophy going back 500 years before the birth of Jesus. The concept of the Logos was found in multiple schools of Greek philosophy and was well established among the first century Greeks. In particular, the Stoic Philosophers [not to be confused with Hiccup’s father Stoick in How to Train Your Dragon] held that the Logos was the divine principle behind the universe. The Stoic Logos animated the universe and penetrated all that exists. Recasting the Logos, the active reason and impersonal God which animated the universe, into human form as Jesus, is John’s great contribution. God, as an intellectual abstraction, was correctly synthesized into a personal, loving Christ.

The Letter to the Hebrews. The author of Hebrews was well educated in Greek thought. The Greek philosopher Aristotle is considered the father of deductive reasoning. Hebrews utilizes Aristotelian logic, what we call Booleans today, far more extensively than any other Biblical writer. Hebrews 1:1-13 is a long logical argument for the Son’s superiority versus the Angels using logical ANDs and ORs. Chapter 7 also begins with an impressive logical argument. Additionally, parallels to Platonic thought are found in the Letter to the Hebrews. Hebrews 8:5 is a good example.

The Letters of Paul contain quotes that almost certainly originate from Greek philosophers. In particular, see 1 Corinthians 15:33, Titus 1:12, and Acts 17:28. The ESV translation provided by BibleGateway lists the Greek philosophers for these verses in the footnotes. Recall Paul’s visit to Athens recorded in Acts 17. Athens was the intellectual and cultural center of the classical Greek world. Stoic and Epicurean philosophy continued to thrive in Athens at the time of Paul’s visit. Stoicism was the foremost moral philosophy of the Roman Empire during the time the New Testament was written.1 Additionally, the city of Saul’s birth, Tarsus, was an important seat of Stoic philosophy. In Acts 17, Paul interacts with Athens’ men using the Greek language, Greek thought, and quoting from Greek philosophers.

We have a pervasive Greek ecosystem in the first-century Mediterranean world. For the Gospel to expand beyond Palestine, the Greek mind needs to understand the relevance of Christ. New Testament authors turn to the Greek language. They will need to utilize concepts that this culture can understand. Ideas, including identifying the Son of God as the agent of creation. How is this identification made?

Go back in time four hundred years before the birth of Jesus to the Greek philosopher Plato. With Socrates and Plato, philosophy takes an interest in God and the human soul. “They [the Church Fathers] began to remember that it had been Plato who made the world of the soul visible for the first time to the inner eye of man, and they realized how radically that discovery had changed human life. So, on their way upward, Plato became the guide who turned their eyes from the material and sensual reality to the immaterial world in which the nobler-minded of the human race were to make their home.”2 An example of Platonic thought found in The Letter to the Hebrews is Plato’s Theory of Forms. With the Theory of Forms, the concept is that an ideal domain or reality exists outside of our material world. Ideas, or true Forms, in this ideal world, are eternal, unchanging, pure, non-physical, and perfect. For those of us in the material world, these perfect Forms are not perceptible by our senses, only by our minds. These Forms may be made manifest in our material world in a way that is perceptible to our human senses. However, if made manifest, the results in our domain are an imperfect copy of their perfect counterparts in the ideal domain. For example, a red ball in our realm participates in the Forms of both roundness and redness. Copies of the true Forms in our material world are subject to change and degradation. The red ball is neither perfectly round nor does it perfectly reflect the essence of the true red Form. Overtime, the shape and color of the ball change.*

As an illustration, the Theory of Forms may be applied to the Old Testament. In Exodus, God gives Moses the design for the tabernacle, the Ark of the Covenant, and the furnishings for the tabernacle. Moses grasps instruction from the Lord concerning the construction of the tabernacle and its furnishings. The perfect Form, created by God, was then transferred from God’s mind to the mind of Moses on Mount Sinai. It is then Bezalel, the chief artisan filled with the Spirit, who renders the tabernacle and its furnishing, making them perceptible to the human senses. God’s mind holds the perfect Forms, which are then communicated to Moses and executed by Bezalel, becoming a material rendering of the ideal Form. Bezalel’s rendering is now subject to time, degradation, and theft, as in the case of the Ark of the Covenant.

God is the creator, Bezalel, in the agent of creation, the individual through whom the tabernacle and its furnishings were made material.

The Exodus example above comes from Philo or Philo of Alexandria. Philo was a Hellenistic Jewish thinker and philosopher who lived in Alexandria. His birth is dated as approximately 20 BC, with his death at around 50 AD. He is a significant Jewish Philosopher residing in the intellectual center of the Hellenistic world.

Alexandria, Egypt, was “the location of the single largest Jewish community outside of Palestine.”3 During Philo’s life, the Jewish population of Alexandria was estimated at 1 million people. The Septuagint, an early translation of the Old Testament from Hebrew into Greek, was created in Alexandria. Think of this text as the standard Greek translation of the Old Testament. Alexandria was also a center of Jewish philosophy. Philo was likely the most famous Jewish philosopher in the Alexandrian community at that time.

Philo wrote extensively.3 His work strives to fuse Platonic thought and Old Testament Scripture. His thinking, which also incorporated Plato’s Theory of Forms, was known to the early Christian Church. Philo’s work likely influenced the author of the Letter to the Hebrews and the Gospel of John in terms of subject matter, but not necessarily doctrine.

Again, it was Philo who applied the Theory of Forms to the Exodus 25 passage. Recall, Exodus 25 concludes with the Lord’s instruction to Moses, “And see that you make them after the pattern for them, which is being shown you on the mountain [Sinai].” Philo comments, “Therefore Moses now determined to build a tabernacle, a most holy edifice, the furniture of which he was instructed how to supply by precise commands from God, given to him while he was on the mount, contemplating with his soul the incorporeal patterns of bodies which were about to be made perfect, in due similitude to which he was bound to make the furniture, that it might be an imitation perceptible by the outward senses of an archetypal sketch and pattern, appreciable only by the intellect;”.3

Creation, the Universe, also begins as a perfect Form in the mind of God. (Separately, here is an interesting article which connects the concept of the Multiverse, with a time dimension, to the third century BC Stoic Philosopher Chrysippus.) But now we need someone with access to the mind to God to take the plan, the perfect Forms, from the mind of the Father and bring it into existence.

Likely the most developed doctrine of Philo is his work on the Logos. For Philo, the Logos, among other things, is the mediator between God and the world. For Philo, the Divine Logos is the agent of creation. The Genesis creation existed in the mind of God as an idea, a Form. The Logos rendered the Form into that which is perceptible to the human senses. It is through the Logos that the universe was made manifest.

Philo writes, “The incorporeal world then was already completed, having its seat in the Divine Reason; and the world, perceptible by the external senses, was made on the model of it [the idea in the mind of the Divine Reason]; and the first portion of it, being also the most excellent of all made by the Creator [the Divine Word or Divine Logos], was the heaven, which he truly called the firmament”.3

Philo gives us an academic Logos, who is the agent of creation.

Why is this interesting? We find a shared subject matter between Philo and our New Testament authors. Consider John’s Gospel. In John 1:1-3, we have, “In the beginning was the Word [logos], and the Word [logos] was with God, and the Word [logos] was God. 2 He was in the beginning with God. 3 All things were made through him, and without him was not any thing made that was made.”

The New Testament Scholar and Theologian C. H. Dodd contends that the introductory verses of the Gospel of John cannot be fully understood and appreciated apart from the ideas of Hellenistic Judaism, especially Philo.

Dodd writes, “It seems clear, therefore, that whatever other elements of thought may enter into the background of the Fourth Gospel, it certainly presupposes a range of ideas having a

remarkable resemblance to those of Hellenistic Judaism as represented by Philo.”4

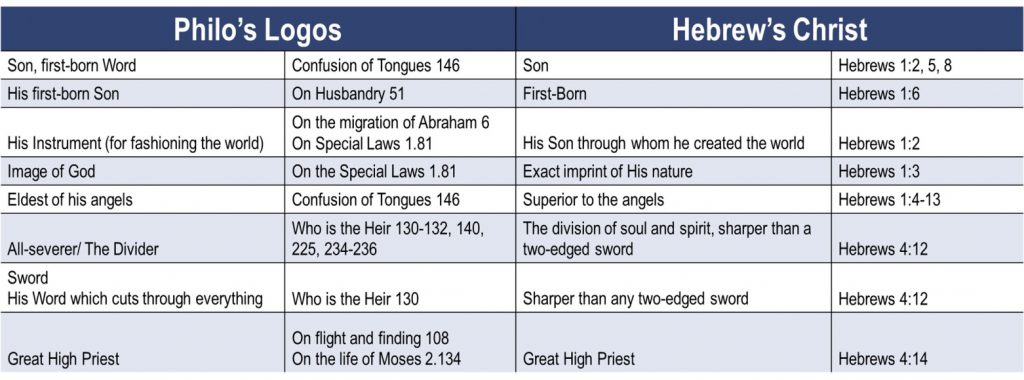

Now, look at the Letter to the Hebrews. The table below compares Philo’s Logos with Hebrew’s Christ, the Son.

The three New Testament authors above are highly intelligent individuals inspired by Christ and the Holy Spirit. My best guess is these authors picked up useful fragments from existing Plato and Greek philosophy, Philo, and, together with the Holy Spirit’s influence, synthesized these elements into the truth who is Christ. They borrow subject matter but not doctrine. Also, whatever fragments they borrowed helped make the message of God’s truth relatable to the Greek audience of the day coming into the Christian church.

What about Paul?

The Colossians 1:15-16 passage and others cause us to speculate that Paul drew his subject matter from Philo. Evidence of affinities between Philo and Paul are thin. Paul seems to develop his thought independent of Philo while, as Henry Chadwick puts it, fishing from the same pool of thought. Paul, the traveler, was ever emersed in a culture familiar with Stoic philosophy. He likely developed his thinking by adopting fragments of Greek Philosophy, including the Stoic Logos, and integrating this subject matter with Old Testament Scripture in parallel with Philo.

Other Views

There are volumes written on Greek philosophy and Philo’s influence on John, Paul, the author of the Letter to the Hebrews, and Christianity in general. The spectrum runs from little effect, to without Greek thinking and Philo’s work, Christianity would not have spread.

An introductory book by Werner Jaeger is given below.

*Theory of Forms

The scholarly theological commentaries on the Letter to the Hebrews agree that the author incorporates Platonic thought. The theologians are split on whether passages like Hebrews 8:5 utilize the Theory of Forms.

As summarized in Douglas Soccio’s book, Archetypes of Wisdom: An Introduction to Philosophy, “However, exactly what Plato meant by ‘Forms’ has remained a subject of intense philosophical debate and disagreement from Plato’s time to ours.” Indeed, the debate extends to Christian theologians as well.

References

- Grant, Frederick C. 1915, St. Paul and Stoicism, Page 274. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Jaeger, Werner. 1961, Early Christianity and Greek Paideia, Page 46. Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Philo. 2000, The Works of Philo: New Updated Edition (Translated by C. D. Yonge). Peabody, Massachusetts: Hendrickson Publishers.

- Dodd, C. H. 1953, The Interpretation of the Fourth Gospel, Page 73. London, England: Cambridge University Press.

Short Introduction to Early Christianity and Greek culture

For further reading, Werner Jaeger’s book, Early Christianity and Greek Paideia is a good introduction by a fine classicist.